|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Profile

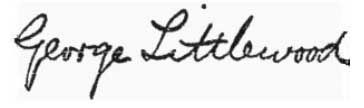

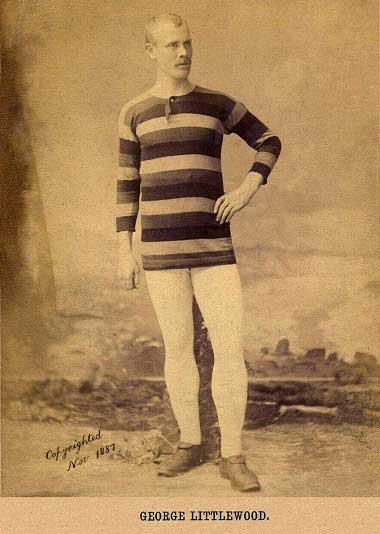

| George Littlewood 1859 - 1912 Born: Rawmarsh, Yorkshire, England |

|

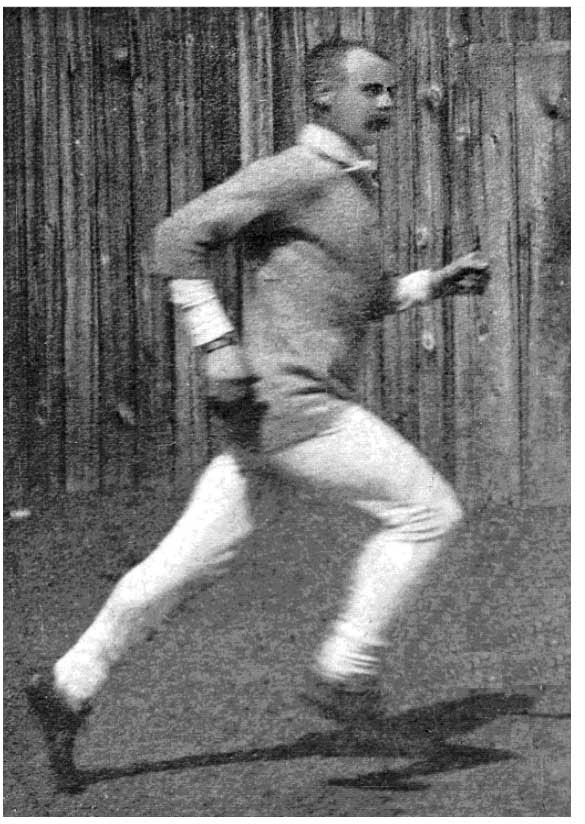

The 'Sheffield Flyer'

by P. S. Marshall

It's called multiday racing today. However, 150 years ago, it was called long-distance pedestrianism and the man who inspired the blue riband event in the sport, the six-day race, was the then incredibly famous American 'walkist' from Providence, R I- Edward Payson Weston.

It's called multiday racing today. However, 150 years ago, it was called long-distance pedestrianism and the man who inspired the blue riband event in the sport, the six-day race, was the then incredibly famous American 'walkist' from Providence, R I- Edward Payson Weston.

The then world-famous sporting superstar was just 40 years old in 1879, when, for the first time in his professional career, he actually ran to claim a new world record of 550 miles in six days around an 8-lap to the mile sawdust track at the Agricultural Hall, London, to win the Astley Belt.

By the 1st of December, 1888, that world record had been broken many times.

"Blower" Brown, of Fulham, England, added three miles in 1880. Frank Hart, aka "Black Dan" of Boston, MA, upped the tally to 565 soon after. Then Charlie Rowell, the Englishman, who had made $50,000 by winning two races at Madison Square Garden, New York, in 1879, banked even more money when he added a mile to Hart's score later that year. The 'Cambridge Wonder' wasn't in the race when John ('The Lepper') Hughes made it 568 in 1881, nor when the 'Brooklyn Cobbler', Robert Vint, ran 10 more miles to make 578 in the same year. The Irishman, Patrick Fitzgerald would add his name into the record books with 582, before George Hazael, an Englishman, became the first person to break the 600-mile in six days barrier. That was achieved at Madison Square Garden, in 1882. Fitzgerald would reclaim the honor with a staggering 610 miles two years later, but it wasn't until February, of 1888, that an American, from Philadelphia, made mincemeat of that score with a staggering 621 and ¾ miles. His name was Jimmy Albert.

But could it be beaten? Well, yes it could!

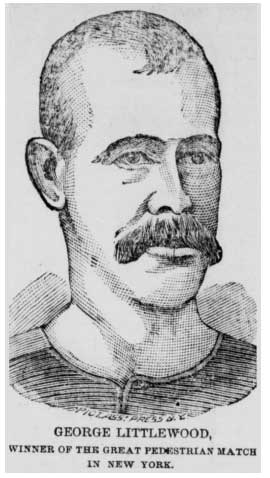

The man who would eventually accomplish the feat was called George Littlewood, and on the 125th anniversary of his remarkable achievement, this is the story of how the 'Sheffield Flyer' managed to add two more miles to that total and keep the world record for almost 100 years!

George was born on 20 March, 1859, in Rawmarsh, Yorkshire, England. He moved to Attercliffe, a suburb of Sheffield, seven miles away, when he was two years old, where his father, Fred, a useful runner in the local pedestrian events, would have taken his son to the well-attended races where the runners would be handicapped according to previous performances. Betting was common and the thousands that turned up to watch them perform would have a wager on their fancied athletes who battled it out for cups, medals, ornamental belts and prize money. Fred was a useful short-distance runner and George would have been excited at watching his dad winning a race and even more excited when he was hoisted above the crowd as they cheered his victory.

Dads, being dads, will always urge their kids on to perform well in sports that they are good at themselves. Fred was no exception. He wanted George to be better than he was, so he pushed him from an early age to succeed in a professional sport that if you were really good, you would be handsomely rewarded.

As a schoolboy, George excelled in other sports, including boxing, cricket and wrestling, but it was in the field of athletics that he showed the most aptitude for - especially running and fast walking - which he displayed a real talent for.

Sheffield is surrounded by beautiful countryside and, in particular, moorland, where, at the age of eight, the young lad was encouraged to run alongside the hounds in local hunts by his father who would watch from a distance as his son, possibly wearing breeches, a white collarless shirt and jockey cap, pursued a fox with other boys, men, and riders on horses.

George's training regime would be meticulously planned by Fred. It would be both daunting and vigorous. Attercliffe was an industrial area where Steelworks were in abundance. A canal runs through its heartland and the towpath adjacent to it would have been the perfect place to put the budding champion through his paces.

It was during one of these training sessions that the boy complained to his dad that his muscles were sore and that he couldn't carry on. But his father knew if George could prove to himself that he could overcome the pain barrier, the experience he was about to put him through would prove valuable for his future career. So he offered George the carrot of a financial reward to get him through it.

"If you're going to be the best one day son, you've got to do better! If you can catch me, you can have this halfpenny. If you really want it, you can get it. Do you want it?"

"Yes dad, I want it."

"Then catch me up and it's yours!"

Fred set off running and George went after him and when he caught his dad up and passed him, he was given his prize for his determination.

With that experience in the bag and with a 40-yard start, the now 9-year-old went on to beat the 12-year-old half-mile champion of England, and 27 others, in a half-mile handicap running race for £15 in front of a big crowd.

As the years rolled on, Fred continued to nurture his son as he dedicated his spare time to perfecting George in the art of foot racing. His dedication paid off when, at the age of 16, George won his first long-distance heel-and-toe walking event and was awarded a silver cup donated by several Sheffield publicans.

Watching the boy perform that day, a local judge said of him: "He is completely genuine, without any deviation from the strict laws of walking."

George's mother had a favorite butcher. She swore by the meat he sold and having no real means of refrigeration, needed the meat fresh. But, there was a big problem. The butcher's shop was 17 miles away in Doncaster! As she couldn't afford to go and collect it on the three days she would have liked to, the solution to the problem was easily found in George's young legs which were the perfect mode of delivery. So, and during the next four years, and as part of his punishing 200 miles a week-plus training regime, the boy would run to Doncaster and back three times a week in a 34-mile round trip - before breakfast!

Later in his career, one of his trainers, Fred Bromley, whilst talking about the influence of diet in the performance of an athlete, once told George: "If you want to raise a lot of steam and power, you must stoke the coals on the fire!" Indeed, there were reports that during his races, his mum would be on-hand to cook her son's favorite meal of chicken fricassee for him.

With his stamina built up by November, of 1879, the then 20-year-old athlete would appear in his first ultra long-distance race - a six-day, 72-hour, 12 hours per day, 'go-as-you-please' (run and walk) event. Along with 27 other contestants, he would make his way round a 19-lap to the mile track at the Drill Hall, Wolverhampton, near Birmingham. An established "ped" called Sam Day would win the race and £50 for doing so with a record score of 360 miles. But it was Littlewood's name that was scribbled in the notebooks of 'sporting men' as he took home fourth prize money of £4 for scoring 275 miles in the allotted time; his performance attracting attention of reporters who wrote:

'Littlewood is a very well built young fellow and such a good natural walker, that he ought, in time, to make a name for himself'.

And.

'With more experience, Sheffield's George Littlewood will make the top grade and challenge the best in the world.'

In February, of 1880, George appeared in his next race, at Nottingham, where, in a 7- day, six hours per night 'go-as-you-please' contest, he came in 5th of 19 runners winning £2 for scoring 252 miles - just 18 miles behind the winner - George Cartwright - the 'Flying Collier'.

But he needed to win and when he did a couple of months later in a circus rink at Leeds, Yorkshire, he did it in style creating a new 12 hours per day, 72-hour, world record of 374 miles. Beating twelve others for the £35 first prize - plus an extra prize of £10 for beating the record, George would publicly state some years later that this was the greatest race he ever won - accomplished on a 38-lap to the mile track. Incredible!

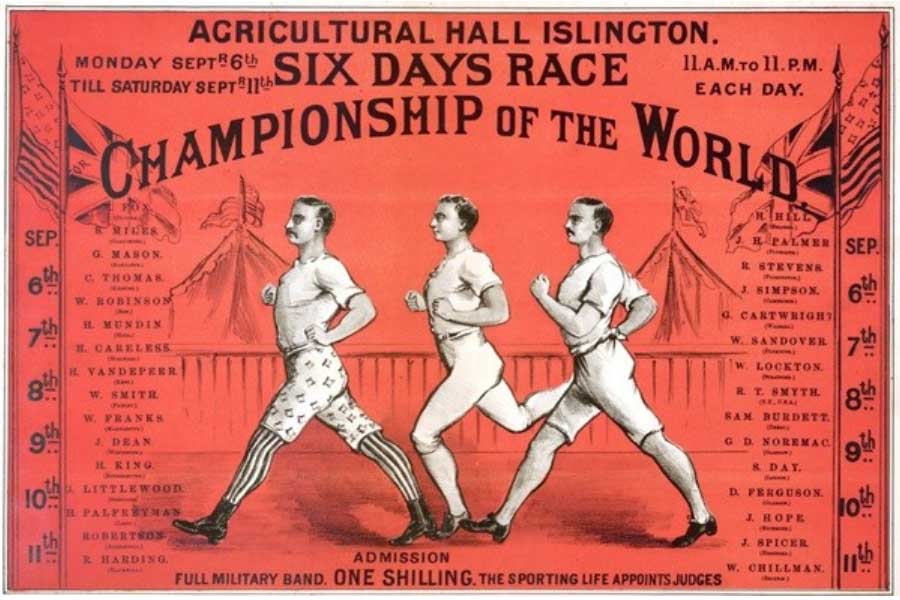

With his first victory secured, he made his first trip to London, where, in September of the same year, and competing in field of 29 at the Agricultural Hall, Islington, the 21-year-old won the 72-hour Sir John Astley 'Champion Gold Medal' and prize money of £60, which included £10 for beating the then current world record of 405 miles by 1¾ miles.

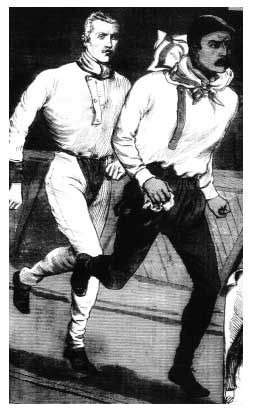

Charlie Rowell (shown left wearing a cap in front of Littlewood), another Englishman (who would think nothing of jogging 150 miles on the first day of a race), was being touted as the favorite to win the 6th international version of the Astley Belt against some very good American athletes, "Blower" Brown and Littlewood - whose connections had entered him into the 142-hour, sixday 'go-as you-please' contest, again at Islington's "Aggie". It would be George's first crack at the 142-hour contest and he did amazingly well to finish runner-up to Rowell, six years his senior, who won the belt with a score of 566 miles. The 'Sheffield Flyer' would manage 470, but it was

a great introduction to the blue riband event and he would have been very happy with second prize money of £155.

Charlie Rowell (shown left wearing a cap in front of Littlewood), another Englishman (who would think nothing of jogging 150 miles on the first day of a race), was being touted as the favorite to win the 6th international version of the Astley Belt against some very good American athletes, "Blower" Brown and Littlewood - whose connections had entered him into the 142-hour, sixday 'go-as you-please' contest, again at Islington's "Aggie". It would be George's first crack at the 142-hour contest and he did amazingly well to finish runner-up to Rowell, six years his senior, who won the belt with a score of 566 miles. The 'Sheffield Flyer' would manage 470, but it was

a great introduction to the blue riband event and he would have been very happy with second prize money of £155.

George's first trip over to America to compete in the '2nd O'Leary International Belt' contest at Madison Square Garden, in May, of 1881, would end in failure, because although starting the favorite, he would only managed to make 480 miles before retiring hurt due to a foot injury. Many said he would have won it. If only.

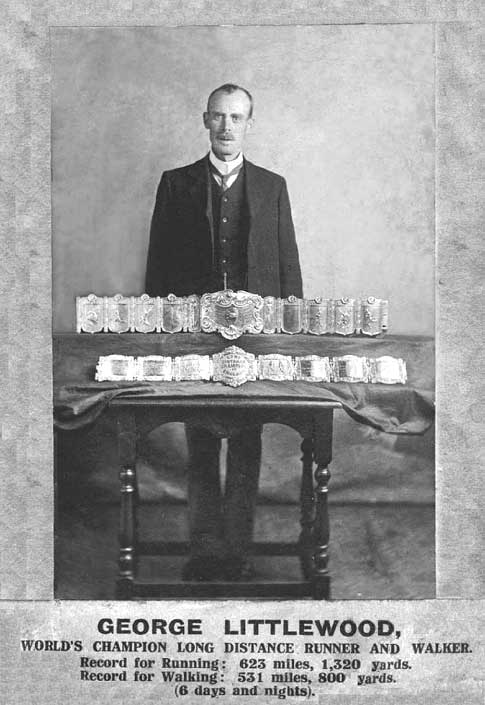

In his next race - a 142-hour heel-and-toe walking match against five others in March, of 1882, at the Norfolk Drill Hall, Sheffield, George managed to make 531 miles on the 13-lap to the mile track. That was one mile better than Charles Harriman's previous world record and it still stands today!

He then competed in the 1st, 2nd, 3rd, 4th and 5th 12 hours per day, 72 hours per week 'Long-Distance Astley Belt' races, which took place in Birmingham, London and Sheffield, between 1882 and 1884, securing the belt outright for winning it three times on the trot.

In 1885, Littlewood took on Rowell again in the 'International Pedestrian Tournament' (Retired) and then again in February, of 1887, in the 'International Pedestrian Go-As-You-Please Tournament' (Won) - both races being held at the Westminster Aquarium, London.

After those races he went back to America for the second time - firstly to Philadelphia where he annihilated the opposition in the 'Championship of the World Sweepstakes' in November, of 1887, before returning to New York to compete in a race at Madison Square Garden, in May, of 1888, where he broke the 600- mile barrier for the first time despite running on a raw bone in his foot.

A staggering 39 competitors stood at the starting line at the same venue on the 26th of November in the same year to try and win the 'Fox Diamond Belt'. One of them was Littlewood and all eyes were on the race favorite as he set off determined to win at all costs.

At the end of the first 24 hours, George had only managed to score 122 miles - 15 miles short of his personal target and 13 miles behind the leader. That was because he had been poorly due to drinking a bottle of beer that had "gone off". As Fred bathed his sons sleeping son's head in vinegar, the bookmakers adjusted their odds and 8/1 was chalked up next to his name on their slates. When he woke up, and now feeling much better, George took the price about his chances before he bounded back on the track in his pursuit of glory and a new world record. That 13-mile gap was extended to 22 miles by midnight on the second day with E. C. Moore leading the race with 240 miles. But then Littlewood got down to work. With his stomach problems seemingly over, the then 10/1 shot in the race started to make ground and, by midday on that third day, Moore's lead over the pre-race favorite had been reduced to 17 miles - and by midnight, to just 3 miles. |

|

"Even money Littlewood" was the cry from the ring, but from there on, and despite being seven miles down on Dan Hearty at one stage, the writing was on the wall and it was George who would take control of the race to win in spectacular fashion in front of thousands of screaming spectators - 623¾ miles and a new world record - a record that was eventually broken by Yiannis Kouros in 1984, in totally different circumstances.

Part of the New York Times headline about the race the following day read: .'Could have covered 650 without trouble.' and if George had been allowed to stay on the track, his world record may well have still stood today.

---------------------

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/George_Littlewood

The 'Sheffield Flyer' is the current holder of the world's OLDEST athletics-based WORLD RECORD of 531 miles - made in March, 1882!

A free PDF of how he achieved this remarkable achievement (Chapter 36 of King of the Peds -- 'Walking on Top of the World!') is available at www.kingofthepeds.com

RP

News | Articles | Trivia

| Profiles | Vintage

Video | Vintage Photos | Contact

Us | Site Map | Home

Cards | Posters

| Autographs | Books

| Pins | Prints

| Authentics | Sportscasters

| How to Order

©

Running Past LLC All Rights Reserved mail@runningpast.com